The “Good” Minority: Asian Americans’ place in America’s racial hierarchy and why that leads to anti-Blackness

The “Good” Minority: Asian Americans’ place in America’s racial hierarchy and why that leads to anti-Blackness

By Ally Mark and Nicole Tiao

To continue our investigation into what it means for AAPIs to fight racism, we are thinking about several questions in today’s article. How does the AAPI community prop up systemic racism? What does our anti-Blackness look like, and how is anti-Blackness perpetuated in the Asian American community? How do the Model Minority myth contribute to Asian anti-Blackness?

(Before we dive in, we want to acknowledge that we cannot speak for the entire AAPI community. “AAPI” is a broad category that incorrectly implies a singular narrative and experience. In reality, this term masks many ethnic groups and a wide diversity of nuanced experiences. As third-generation Chinese Americans, we will speak from our East Asian experience and center on East Asian anti-Blackness.)

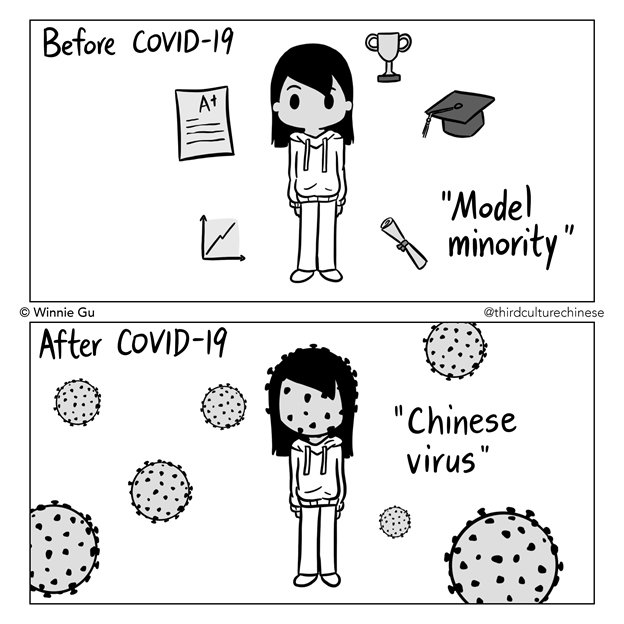

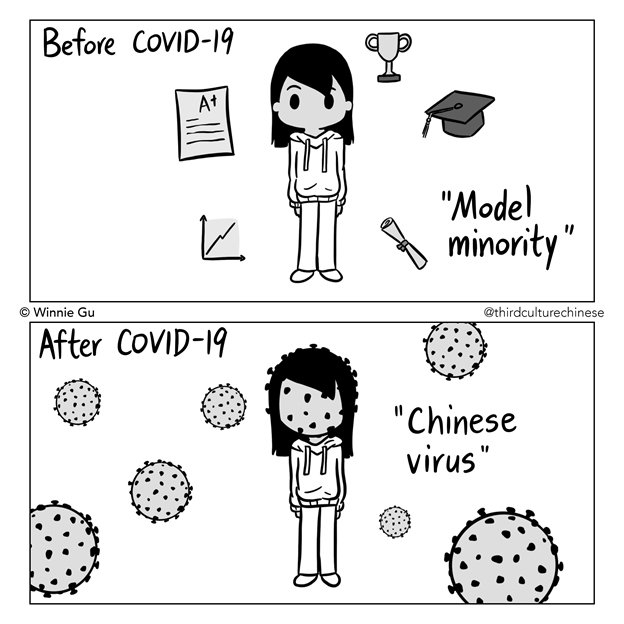

Racism in the time of COVID-19

COVID-19 exposed for many Asian Americans the intense xenophobia and racism brewing against our community. The discomfort of not quite belonging. The constant awareness of being seen as “foreign” or “not fully American.” The subtle pressure of representing one’s entire ethnicity or culture. Suddenly, this ever-present “subtle racism” turned into physical hate crimes. People across the political spectrum rushed to place false blame on Asians for coronavirus, egged on by President Trump and so-called “leaders” around the country.

AAPIs and civic organizations quickly rallied to combat the anti-Asian hate crimes. But coordination within our own communities is not enough: the racist rhetoric and physical violence that arose under the COVID-19 pandemic are pulling back the curtain on the model minority myth. Many Asian Americans are seeing it for the first time for what it really is: a dangerous lie.

When Asian Americans are praised for success due to “hard work, good schooling, and staying out of ‘trouble,'” society is saying there is a “good” way to be a minority. Of course, then, there must be a “bad” way to be a minority. By positioning Asians as the “good” minority, white America is telling Asians that we are still inferior and will never quite be seen as “American.” Unspoken is the classification of Black and brown Americans as “bad” minorities.

Using the model minority myth as a racial wedge between Black folks and AAPIs has received lots of scrutiny recently. Source: NPR

COVID-19 reminded us that the more day-to-day, “casual” discrimination leveled at us is a veiled form of xenophobia. And we cannot forget that this discrimination was created to uphold a country built on white supremacy and keep power from the hands of people of color.

What is white supremacy, and how do Asians interact with it?

The structure of white supremacy underpins our society, privileging whiteness and reinforcing its power and influence. No matter how hard we work or how many degrees we attain, the status of AAPIs in America is inseparable from America’s racial hierarchy that elevates whiteness and devalues Blackness. So, while the racism that Asian Americans face usually does not manifest in physical harm, as it does for Black and brown folks in the US, our place here is still that of the “Other.”

As a result of this hierarchy, our community inevitably engages in and supports anti-Blackness and white supremacy. We aren’t trying to discount the AAPI struggle against racism. However, we want to make clear how Asian Americans knowingly and unknowingly participate in–and benefit from–white supremacy and anti-Blackness. Anti-Blackness boils down to one simple idea: only Whiteness is truly valued.

Asian anti-Blackness, informed in part by old cultural prejudices, has created a culture privileging paler skin and beauty product lines of skin whitening creams. Source: The Juggernaut

Asian (particularly East Asian) anti-Blackness is complicated, ranging from beliefs in damaging, racist narratives to outright discrimination to economic and social exclusion of Black people. Think, for example, about the long-standing value placed on pale skin. Or the classic idea of “work hard, keep your head down.” Many Asians undoubtedly overcame incredible challenges to create a life for themselves in America, but this success lulls many into believing in a false narrative that hard work can overcome any obstacles, ignoring the structural racism that holds back Black, brown, and Asian folks. Yes, this same structural racism holds AAPIs back too, from maintaining the “bamboo ceiling” to stereotyping AAPIs as the perpetual outsider.

How does the Model Minority myth lead to anti-Blackness?

The model minority / ”American Dream” narratives fall apart when we reframe the differences in how AAPI and Black communities experience racism, and how many differential outcomes are engineered by white supremacy and structural racism. After World War II, white racism against Asians began to decrease in some regards and accordingly, the wage gap between Asian American and white workers slowly narrowed. After decades of earning the same lower incomes as African Americans, Asian Americans who suddenly earned higher wages were not doing so because they were ‘working harder’; it was simply a matter of white America becoming less racist.

Source: Washington Post

In the 1960s, because of the Civil Rights Movement, the U.S. government reformed its immigration policy to allow, for the first time, many Asian immigrants from specifically educated, highly-skilled backgrounds. Housing discrimination was rendered illegal and segregated white neighborhoods slowly opened up, first to Asians, then, later, to Black and Latinx folks. This exclusivity permanently shaped the AAPI community. White Americans started marveling at Asians’ upward mobility, and Asians and whites alike pointed to the change as ‘proof’ that hard work could overcome circumstance. After that, Asians started benefiting from their newfound access to neighborhoods with better funded schools and public spaces.

These policy changes and shifts in attitude show how Asians literally got closer to whiteness. However, white America’s praise of Asian Americans for their hard work and quiet successes was self-interested. With the Cold War looming in the background, America needed to pretend that it upheld its values of freedom and equality, which meant papering over the ongoing Civil Rights Movement. These factors — not educational attainment — helped create the propaganda of the model minority myth.

Unfortunately, many AAPIs bought into this narrative. Many sought to demonstrate their upstanding citizenship and believed they had earned greater acceptance in America. The flip side of believing you can work hard to earn success was assuming that Black communities are lazy and at fault for their poverty, crime, and drug problems. Thus, the model minority myth pitted Asian Americans against Black and brown Americans, and allowed white America to dodge talking about racism in an honest way.

How do we move forward from here?

There’s hope for healing this divide and for strong allyship between our AAPI communities and Black communities. When Japanese Americans emerged free from their internment camps after World War II, their release gave birth to generations of activists who leapt into a decades-long fight for reparations. Ultimately, the government relented, laying the groundwork, the advocacy infrastructure, and the precedent for future reparations.

On February 20, 2020, the California Assembly apologized to for racial discrimination against, and participation in the federal government’s internment of, Japanese Americans. Several survivors and their families joined the ceremony. Source: AP

Certainly, reparations for slavery are more complicated, but the simple fact that America acknowledged its horrific mistake with Japanese Americans means two things. One, we in the AAPI community have a real stake and a historic place in the fight Black and brown Americans are waging against racism. And two, we know an honest conversation about race in America is possible. In fact, it can start right here in our own AAPI community.

AAPI engagement in white supremacy and anti-Blackness is a complicated and delicate topic because we have become the privileged minority. While the underlying causes for that privilege are not necessarily in our power, we can work to remove our own anti-Blackness. My mentor Dr. Shamell Bell said it best, “I don’t think people really want to be free; what I think people want is that they just don’t want to be the one that’s oppressed.” White supremacy maintains its stranglehold by pitting minorities against each other, thereby preventing solidarity against a structure that harms us all. We will unpack this claim in our next blog post, which will address the underlying role of white supremacy in affirmative action.

Ally Mark is an AAAF media fellow, based in Chicago. She is a recent graduate of Northwestern University’s environmental engineering program and now works at a Democratic political communications consultancy. You can find her baking scones and sourdough bread or camping in the woods.

Nicole Tiao is part of the AAAF media team. She is a senior at Dartmouth College with a double major in physics and history. She is currently working for a geography professor and an activist in the Dartmouth Student Union (DSU).

###

Unless clearly identified as statements of the AAA-Fund, the views, opinions, analyses, and assumptions expressed in each blog or clearinghouse post are those of the author or contributor alone, and not those of the AAA-Fund.